Zoochosis affects captive animals like elephants, orcas, and birds, and this psychological condition is a clear sign that wild animals don’t belong in captivity.

From childhood visits to the zoo to viral videos of “smiling” dolphins in tanks, we’re taught to believe animals in captivity are happy, safe, and well cared for. But behind the bars and beyond the glass is a very different story—one where animals are suffering mentally and emotionally. This suffering has a name: zoochosis.

What Is Zoochosis?

Zoochosis is a psychological condition that affects wild animals held in captivity, leading to repetitive, compulsive behaviors not seen in the wild. These behaviors—sometimes called stereotypical behavior—include pacing, swaying, head-bobbing, feather plucking, bar-biting, and even self-mutilation. Zoochosis isn’t just a quirky habit—it’s a glaring red flag that an animal is under extreme stress and emotional distress.

Imagine living your entire life in a space the size of your bedroom, with nothing to stimulate your mind or body. No freedom to explore, no ability to form natural social groups, no way to express your instincts. That’s the reality for animals in roadside zoos, aquariums, and even some of the most “accredited” facilities, and zoochosis is their cry for help.

What Species Show Zoochosis?

Sadly, zoochosis can affect nearly every species in captivity. From polar bears who pace endlessly in small enclosures, to great apes who rock back and forth while holding themselves, the signs are clear and heartbreaking. Even giraffes, big cats, wolves, and reptiles have all displayed some form of stereotypic behavior associated with zoochosis.

Does Zoochosis Impact Animals in the Wild?

Zoochosis is a condition of captivity. Wild animals do not display the stereotypic, compulsive behaviors we see in zoos and aquariums. In the wild, animals engage in complex social interactions, roam vast territories, hunt or forage for food, and choose when and how they rest, play, or raise their young. Zoochosis is a human-made issue, born from our decision to confine wild animals for entertainment, “education,” or profit.

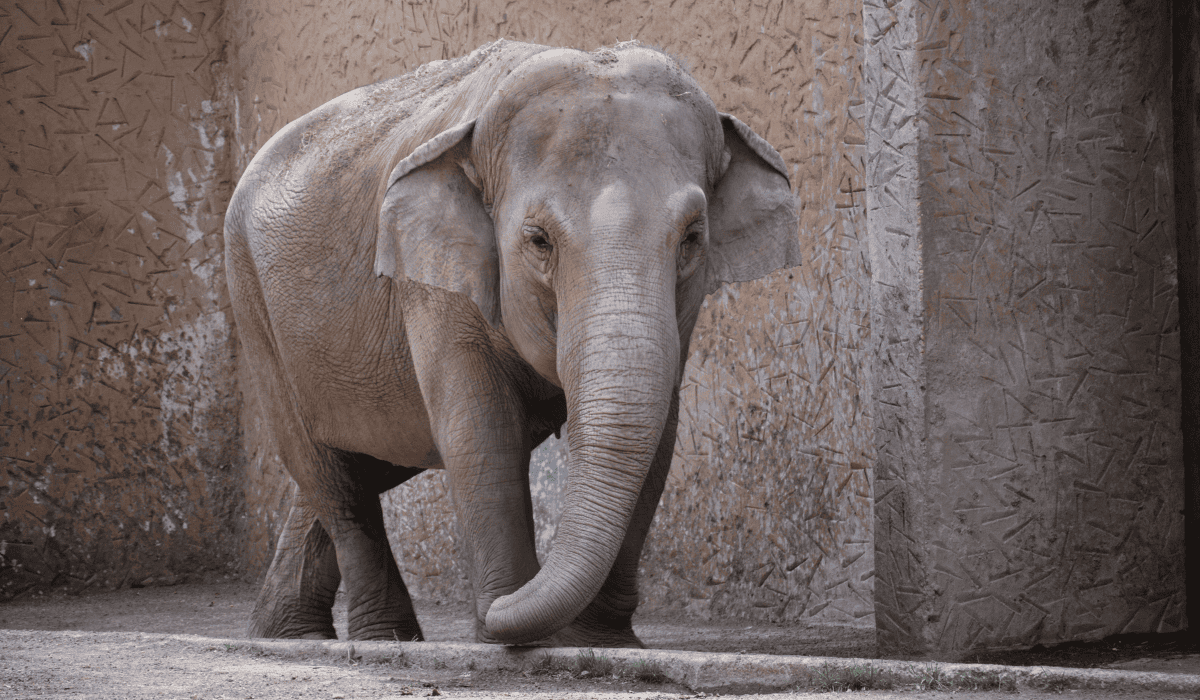

Zoochosis in Elephants

Elephants are among the most intelligent, emotional, and socially complex animals on the planet. In the wild, they roam up to 30 miles a day, form deep family bonds, and grieve their dead. In captivity, they’re often kept in small enclosures, isolated or with incompatible companions, and forced to endure hard surfaces that harm their feet and joints.

The result? Pacing, head-bobbing, repetitive trunk swaying, and aggression—all signs of zoochosis. These are not “cute” behaviors. They are desperate coping mechanisms. And no, even “large” zoo exhibits cannot replicate the freedom and enrichment of the wild.

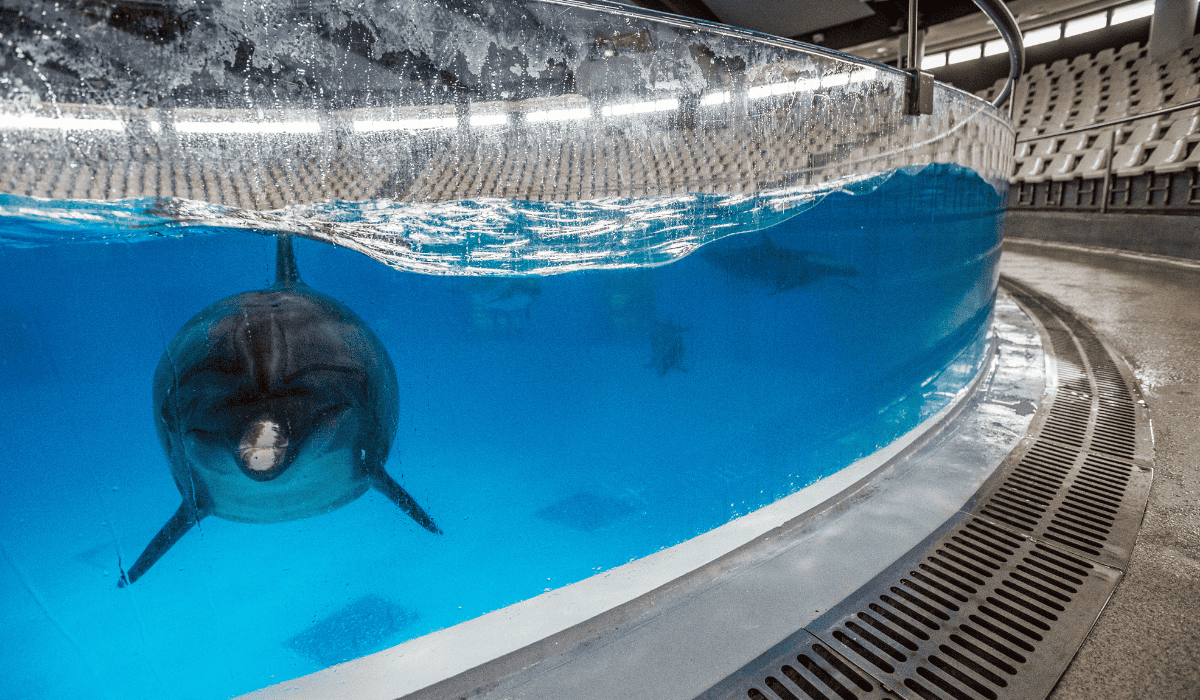

Zoochosis in Orcas and Other Marine Mammals

Image credit: Jo-Anne McArthur / Born Free Foundation / We Animals Media

Orcas, dolphins, and other marine mammals are among the worst victims of captivity—and some of the most visibly impacted by zoochosis. In the wild, orcas swim up to 100 miles a day, communicate using complex vocalizations, and live in tight-knit pods with lifelong bonds.

In captivity, they circle tanks the size of “bathtubs,” float listlessly at the surface, and exhibit behaviors like repetitive swimming patterns, jaw-clicking, and self-harm. Some even gnaw on the sides of their tanks until their teeth are ground down to the pulp. This isn’t conservation—it’s cruelty.

Zoochosis in Captive Birds

Birds, especially parrots, are extremely intelligent and social. They fly miles daily in the wild, solve puzzles, and form strong bonds with their flock. In captivity—especially in small cages with little enrichment—they often suffer from feather plucking, repetitive vocalizations, and self-mutilation.

What’s worse is that these behaviors are often misunderstood or dismissed. A plucked parrot is not being “naughty” or “quirky.” They’re trying to tell us something’s wrong—and we need to listen.

It's Time to End Zoochosis

Zoochosis is a symptom of a system that values entertainment over ethics, and profit over animal protection, but we have the power to change that. We can choose to support true sanctuaries over zoos, advocate for legislation that bans wild animal captivity, and educate others about what’s really happening behind the scenes.

Animals don’t exist for our amusement. They belong in the wild, where they can be who they were meant to be.

Join us in creating a world where wild animals stay wild, because every cage, every tank, and every enclosure is one too many.