As a fundraiser for World Animal Protection, I often share why the Wildlife Heritage Area program matters, but seeing it firsthand gave me a deeper appreciation for this work and brought the vision for this work to life.

A few weeks ago, I found myself in the pitch black, hand in hand with five coworkers and a group of people I had just met, in the middle of the Costa Rican rainforest, trying to adjust my eyes to see the gentle glow of bioluminescent fungus on the ground around us.

This was the grand finale of a magical experience exploring Tapir Valley, a potential site of our next Wildlife Heritage Area. Wildlife Heritage Areas is an initiative developed by World Animal Protection and World Cetacean Alliance that protects animals in their natural habitats, providing tourists with a responsible and humane alternative to exploitative animal experiences.

As a fundraiser for World Animal Protection, I can recite the reasons why this program is essential, but experiencing it firsthand brought them to life, transforming my understanding into a tangible, unforgettable experience that I cannot wait to share with others.

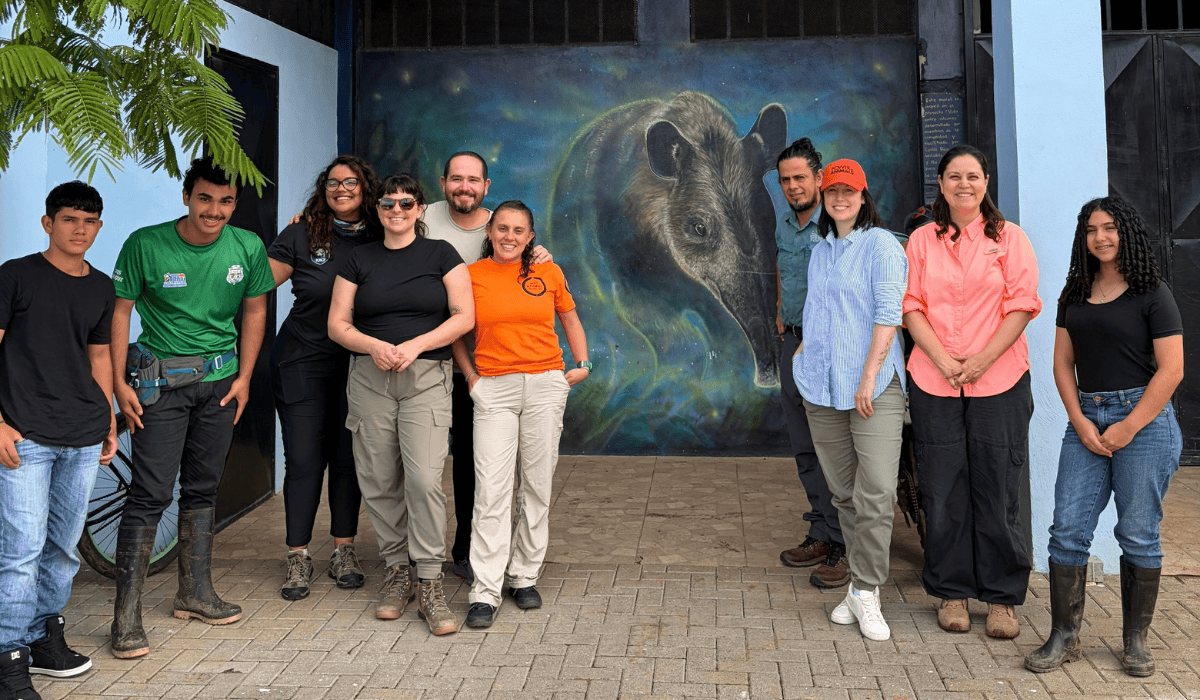

World Animal Protection staff gather with the Tapir Valley community leaders in front of a mural of a tapir.

A group of World Animal Protection staff gathered with the local community members to hear how this site—Tapir Valley and its wider community of Bijagua—came to be, which protects beautiful, unique animals called tapirs, as well as ensures a biodiverse landscape for tapirs and other wildlife to thrive in. We heard from multiple community leaders and organizations who have come together to protect the tapirs and their natural home: the local Chamber of Tourism, a local NGO, a high-school youth-led organization, and Donald, the founder of the Tapir Valley Reserve, who also supports the Chamber of Tourism and environmental education programs.

Everyone we met was a true community leader—people who, as they jokingly put it, “can’t say no.” It shows in the countless hours they devote to caring for their neighbors, their land, and the wildlife they work so hard to protect. Their deep respect for the natural world is matched only by their commitment to teaching others to share that same respect.

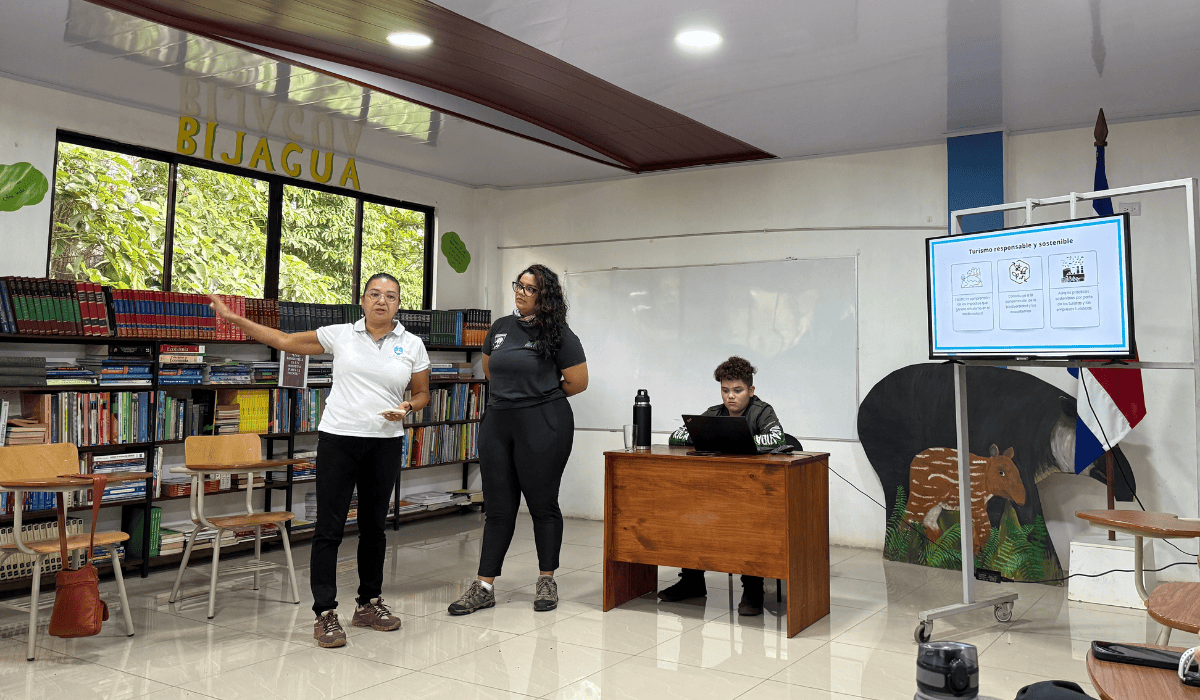

Nillareth Gallardo (left) and Melany Soto (right), who are both part of the Local Chamber of Tourism, telling us about their work protecting tapirs in their community.

Costa Rica may be a beloved tourist destination, but many visitors don’t realize that the wildlife activities they participate in often heavily exploit animals. Sloths, for example, are often taken from their native forests and placed in captivity or moved to smaller, non-native forest patches, so tour operators can guarantee sloth sightings.

We were not guaranteed to see tapirs on our visit to Tapir Valley; without exploiting animals, they, of course, roam free. While we were lucky to see three tapirs, even without that experience, the tour was rich in active jungle life, beautiful scenery, and expert tour guides.

Me at Tapir Valley.

Our tour began at a tree nursery where native plants are grown to strengthen biodiversity throughout the valley. Twenty years ago, the land was used for farming and husbandry, but you would have no idea; the land has been thoughtfully rewilded, a transformation that speaks to the community’s long-term commitment to restoration, as well as wild animal protection.

We were welcomed with fresh fruit and coffee, provided with headlamps and rainboots, and throughout the tour, guided with care, leadership, and safety in mind.

Early into our hike, we saw a pair of tapirs named Paco and Lola, who have been moving around together as a pair. Tapirs typically travel independently, giving the team at Tapir Valley the opportunity to study this unusual behavior.

Tapirs Paco and Lola.

We later saw the indentation in the grass where a baby Tapir named Gaia—just 1.5 years old—sleeps, and Donald, our tour leader, knew this meant she was nearby. We then silently watched as she munched on plants in the darkness.

Gaia, the baby tapir.

Throughout the jungle tour, we were guided through the sunset and then into the darkness, stopping to observe colorful frogs, snakes, birds, and butterflies, with Donald sharing his deep knowledge of wildlife with us. We stomped through mud, crossed over streams, and listened to the sounds of the jungle, including birds, crickets, and the bioluminescent fungus, which, as its name suggests, is a type of fungus that glows in the dark.

A red-eyed tree frog.

This was not your average afternoon hike, nature walk, or tourist destination. This was truly a one-of-a-kind experience that I couldn’t wait to tell my friends and family about. As an animal, wildlife, and nature lover, I felt as though I had been given a gift of seeing into this private world that so few have access to—and the best part was that I knew I was not causing harm by being there, unlike so many other tourist experiences.

This is why we designate Wildlife Heritage Areas: to give people the rare opportunity to witness wildlife in their own space, to protect wild animals and their habitats, and to understand what true coexistence can look like.

I hope you have the chance to visit one too and see what’s possible when communities and wild animals are allowed to thrive together—an experience that stays with you long after you’ve returned home.