Wild Capture, Pet Expos And Our Homes: Ball Pythons Are Suffering In Silence

Blog

Today, hundreds of millions of birds, mammals, fish and reptiles are traded worldwide as exotic pets. Ball pythons are one of the most popular choices, finding themselves confined to glass tanks in homes all around the world.

Guest blog by Cassandra Koenen, International Head of Wildlife. Not Pets Campaign

In many ways, the ball python is the poster child of the exotic pet trade.

It’s the single most traded live animal legally exported from Africa under CITES. Over the past two years, we have been researching and investigating the global systems that prop up this industry and subject ball pythons to a life of cruelty and suffering.

The Cruelty of Commerce

Reptiles are thought to make up around 20% of the global exotic pet trade, yet they are some of the most misunderstood species. Ball pythons are sentient beings and they are able to feel a range of emotions.

Because they are less like people than cats or dogs in both biology and behavior, it’s harder for us to relate to them. They aren’t cute and cuddly by many, so we tend to assign a different value to them.

This often leads owners to misjudge the level of care they need and fail to meet even their minimum needs with respect to space, nutrition, environment, and enrichment.

Myths and Reality

Many people believe that reptiles, like ball pythons, are great starter pets that require little care and attention and they do not feel positive and negative emotions. This couldn't be further from the truth.

The reality is that are far more complex than people often realize, with biology and behaviors that can only ever be fully met in the wild. They require specialized care to meet even minimum welfare requirements in captivity. False claims of their limited intelligence, emotional capacity, and minimal welfare needs can mean that they can suffer considerably.

The belief and trust in these myths results in the unintentional cruelty and neglect of captive snakes. These myths are often used to justify a massive global trade that threatens the survival of these animals in the wild.

Without proper care, ball pythons can experience stress, injury, malnutrition, disease, premature death, deformities, and abnormalities created by selective breeding of morphs and failure to meet minimum standards for captivity (i.e. space, stimulation, water).

It is only in the wild that ball pythons can fully meet their biological needs and exhibit their natural instincts.

The Problem With Morphs

Ball pythons with specific colors or patterns—frequently referred to as ‘color morphs’—are increasingly popular with prospective snake owners and many breeders are willing to selectively breed snakes in captivity to meet this demand.

Unfortunately for the snakes involved, there are several genetic disorders associated with the breeding of these morphs.

For example, "wobble head" syndrome is a nervous system disorder that occurs in spider morph ball pythons. Symptoms include side-to-side head tremors, lack of coordination, erratic corkscrewing of the head and neck, poor muscle tone, and loose tail grip.

Selective breeding can also cause spinal deformities, skull deformities, and “bug eyes.”

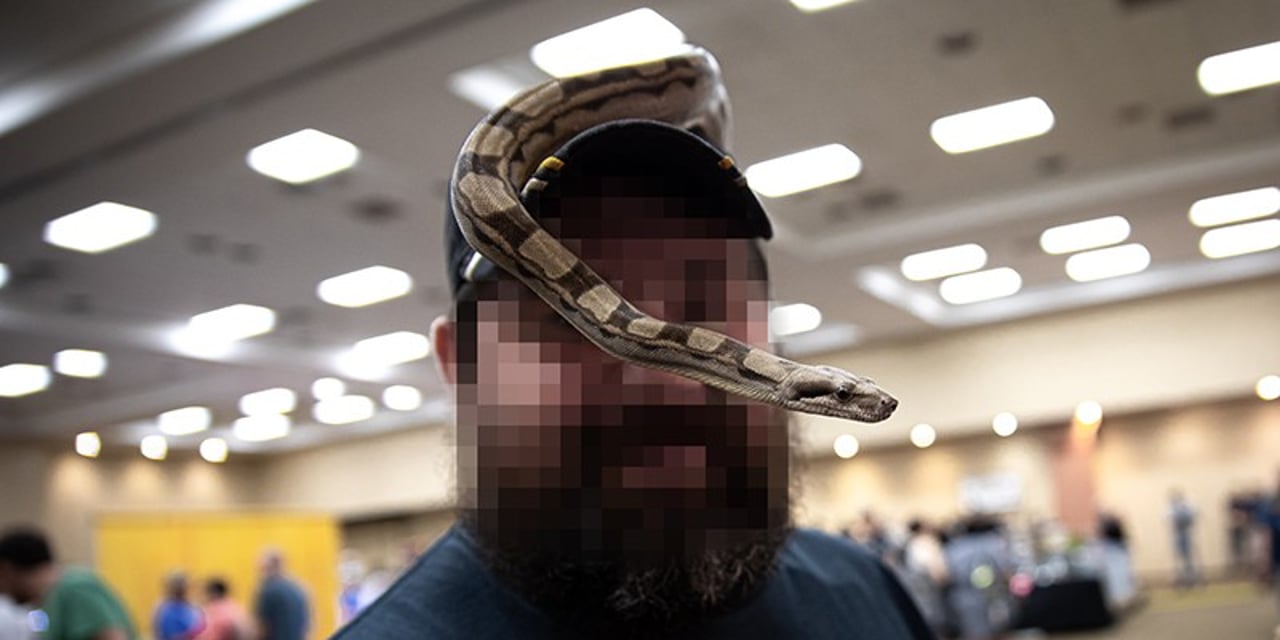

Pet Expo Cruelty

At the exotic pet expos we’ve investigated in Canada, Netherlands, Spain, the US, and the UK, 94% of the animals appeared to be captive-bred morphs rather than snakes that were pulled directly from the wild.

Breeding and selling morphs is lucrative. Depending on characteristics, they can sell for tens of thousands of dollars.

If conversations with retailers are any indication, it’s possible that a very large proportion of ball pythons exported from Africa are being purchased by breeders to discover and breed new morphs, rather than selling directly to homes of potential pet owners.

By introducing wild-caught snakes into the captive-breeding process, many unsuspecting owners may think they have purchased a captive-bred snake, not realizing that their pet was quite possibly sourced directly from the wild or via “ranching” operations in West Africa.

Your Health at Risk

The outbreak of the deadly novel coronavirus highlights how diseases can be transferred to humans from wild animals in the wildlife trade.

It’s important to note that snakes and other reptiles can become vectors of zoonotic diseases that can also make humans sick, while seeming perfectly healthy and unaffected themselves.

Once these animals are sold as pets, owners, and anyone who comes into contact with their pets, is at risk of contracting illnesses like salmonella. After a recent outbreak in Canada, it was revealed that several people had come into contact with pet snakes before they became ill.

Snakes sold at a wildlife market in Wuhan, China, were originally suspected as a potential source of COVID-19.

However, even if snakes are, as now seems likely, "innocent" with respect to COVID-19, our visits to snake farms in West Africa revealed that these facilities do more than just feed the demand for ball pythons as pets.

They also act as wider trade hubs, exporting other wildlife too. Some of these species, like bats, civets and primates, are higher up the human health list of concern when considering their role in earlier epidemics such as SARs in 2002 and Ebola in 2013.

Global Problems Require Global Solutions

Given the complexity of the trade chain for pythons from West Africa to other parts of the world, we need to disrupt the trade from many angles—from transportation and government agencies to online sales and pet shops.

Now is the time for people to stop buying and breeding wild animals as pets, and for governments, organizations, and nations to unite to ban the global wildlife trade—to end the suffering of wild animals and to protect people.

It is time to turn the tide on the exotic pet trade and to stop buying and breeding wild animals as pets and keep wild animals in the wild, where they belong.